Monastic Ireland: The Mendicant Orders

Analysing the world of the mendicants and their lifestyle through a contemporary lens

Mendicants were fascinating and solitary communities who possessed an ornate charm and lived by a vow of absolute poverty and dedication to an ascetic way of life. They believed that they should live in a world of similar absolutes, just like their Lord and Saviour – Jesus Christ.

This entailed renouncing properties and utilising their time by travelling the country to preach. But, how did they survive? The community was almost purely dependent upon the good will of their fellow neighbours, listeners, and followers. In fact, “mendicant,” which is derived from Latin mendicare, literally translates “to beg”.

Unlike their contemporaries, the monks of the Cistercian or Benedictine orders, mendicants preached their philosophies on God in cities. Their dictum was “not to live for themselves only but also to serve others”. So, they were very active in community life-teaching, healing, and helping the sick, poor, and the destitute.

Cities in Europe, regardless of their size, felt the presence of mendicant convents. It is critical to analyse how these institutions reshaped the topographical, social, and economic realities of urban life in the late Middle Ages, how they would also often destabilise the traditional parish organisations, and how they “influenced” the city’s social life.

The mendicants expanded well into new suburbs, while also sometimes settling in the heart of a city, often demolishing neighbourhoods in this process. The 13th century witnessed friars being set up in large complexes within densely inhabited urban spaces. For example, in Italy, they would carve out open spaces (piazzas). Therefore, this article also analyses the process of reconstruction of their presence in terms of their physical, spiritual, economic, and societal influence, even after the systematic and deliberate destruction that began as early as the 16th-century reformation.

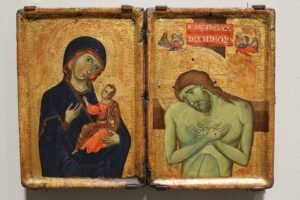

Major mendicant orders, Franciscans and Dominicans, aspired to mimic the life and suffering of Christ. The sight of Christ’s suffering, with the outstretched arms and graphic wounds, were believed to be “mystical”.

The order’s primary mission was the evangelisation of the masses and, for this, the church ceded complete control which freed them from the jurisdiction of the bishops. Henceforth, they travelled around the world in an effort to convert or reinforce the faith. Interestingly, it was on these journeys to the East that the friars first discovered “Byzantine” art, which, consequently, made visual arts gather significant popularity and was further used to reinforce their apostolic mission.

For them, the union of the material and the spiritual was truly advantageous. Art had the power to strengthen existing faiths and more importantly, aid in the conversion of the skeptics. Soon, the monks, who had previously shunned materialistic possessions, gained new perspectives on social class and donned their monasteries with spectacular images, inspired primarily by Byzantine art.

Emergence and rise in importance

The rise of mendicant friars meant a revolution in the religious life of the Church. Previously, different forms of monasticism placed importance on solitude and complete withdrawal from the world which the friars sought to evangelise. The preferred location for these monastic orders was inherently in rural locations. However, the friars soon favoured urban settlements and the newly established university centres wherein they would meet and interact with numerous scholars.

In Ireland, the Dominicans were amongst the first friars to arrive.They established foundations in Dublin and Drogheda in 1224. The Franciscans’ precise date of arrival is unknown, however, the Carmelite friars started appearing in 1271, then followed by the Augustinians.

These friars gravitated towards the regions of the Anglo-Norman colonies, where their linguistic and cultural familiarity with the colonists assured their continued practice of pastoral activities, as well as materialistic gains that supplemented their mendicant lifestyle. Many foundations were also laid in Gaelic territories around this period including the Franciscan houses at Ennis (c. 1240-47), Armagh (1263-64), and the Dominican foundation at Roscommon.

Within the initial “waves”, there were almost 89 friaries established. However, these numbers started to decline at the end of the 13th century due to wars, famine, and the Gaelic revival age.

Main Themes

The primary themes of mendicant buildings in the Middle Ages have been researched in many books on architecture. They are dominated by 3 types of analysis : the first focuses on an individual site, either a single church or a convent as a whole. The second consists of a survey that covers a region or an extended chronological period. Lastly, the third type of study, which was introduced in 1946 by Giles Meersseman, dealt with very specific orders, to a particular building or the entire process of mendicant building practice.

To truly grasp the concept of poverty in the architectural structures of the new orders, legislation on architecture was generated. The rapid expansion of buildings became necessary because the religious communities were flourishing and started gathering a significant following. The primary reason for the ornate and luxurious decorations that adorned churches was said to be because of high-ranking members and patrons’ authority. Consequently, preaching in open spaces saw opposition, especially from the secular clergymen, which made preaching more and more difficult.

The individual site approach can also be looked at after archaeological excavations and through a multi-disciplinary approach. This type of study focused heavily on the identification of systematic approaches concerning architectural planning and design, especially their typologies. Understanding the promulgation and meaning of certain architectural concepts and in what way the concepts were embedded in a ground plan comprehensible to the contemporary user of the space, is necessary to realise that these plans were developed in relation to the functioning of a building.

Individual sites carry with them their own distinct history and, through the works of scholars and archaeologists, these histories can aid us in understanding the particular region better. These authors, thus, have been successful in engaging with the local characteristics whilst also analysing the internationality of the mendicant orders. These local characteristics range from socio-economic factors to communal systems, but all these can be categorised within an international context so that, even though these characteristics may vary from country to country, the identifiable characteristics of the mendicants remain consistent.

Moreover, observing the social and urban role of these friars and how they almost “reconfigured” their surrounding environment is important. Panayota Volti’s study of mendicant architecture in France and the Flanders region provides a refreshed focus on entire convents within their urban setting. Furthermore, Volti also includes the study of the architecture of the Augustinian and Celestinian orders. But why was this important? Almost all mendicant institutions were in direct competition with each other for numerous reasons, including space, funding, and patrons’ authority. They also shared a fairly common approach towards the architecture itself.

Volti reinvigorates focus on well-established convents, though most of the buildings haven’t survived. Her research is, therefore, strongly based on archives and archival images. Her coverage of the social and economic realities of the cities, along with the use of materials, forms a positive and concrete analysis of the very layout of the cities and the erection of the mendicant buildings.

In order to bring to light the effects of emerging mendicant architecture, the study of “one individual site” has been essential, as the first structures were usually rebuilt or added to as the communities grew and flourished. Archaeology serves as another fundamental tool, though it is unfortunately not precise as these sites were usually located within the cities.

The in-depth study of archival sources in terms of archaeologically oriented methods is vital to comprehend the mendicant architecture, especially from the years 1220 to 1270. This period witnessed smaller buildings being consistently replaced by larger ones.

The study of rapid growth and evolution of institutionalisation of the new orders requires analysis of the structural details that reveal chronology and the process at individual sites. The friars felt the need to be innovative and somewhat adaptive to acquire new sites and erect new buildings as they were well aware of their tightly packed urban neighbourhood. Moreover, their concept of poverty diminished significantly as the friars would generate ample income from tithes, rent, and agricultural yields.

The Cistercians, however, set out to tackle this problem through a whole new approach in which they would utilise wide, open terrains where their vision could be executed with minimal opposition.

The idea of constructing friars within major cities was an ideology that the mendicants adhered to, but this required many controversial decisions which led to acquisitions of major houses and properties, consequently affecting the entire neighbourhood. Friars soon began to predict what properties may become available and took charge as medieval “property dealers”. Social relations with the neighbours and the transferring of property soon became integral tools that led to the construction of mendicant buildings within the cities. As a result, the buildings had to be calibrated to what properties might become available in the future.

Initially, the friars would occupy and inhabit donated and abandoned buildings like churches, hospitals, and even homes. However, to accommodate the ever-growing community while showcasing the ideals of poverty, they sought new and aggressive ways to take over bigger buildings. Construction of the churches and convents was also very financially draining and, by the mid 13th century, debt became extremely common amongst these orders.

Theologian, Giles Meersseman, analysed the aforementioned issues and concluded that the construction of these convents was a lengthy process and that many of these convents were being built throughout the 13th and 14th centuries. Mendicant architecture, like the cities, was always in a constant “state of becoming”. Regulations on architecture and design were discussed with each order before progressing, and there was a rather complex relationship between the ongoing projects which were usually underway for decades.

The architectural space that the mendicants created was made, not only to serve the liturgies of both friars and laymen, but also as a way of communicating information through panels and frescoes, which were present in the interiors of the churches. However, the ostentatious decorations rarely survived, making them difficult to study.

In the rare instances that these frescoes have survived, numerous collaborative research has focused on the extant paintings or altars of a single site that help in construction phases and dating. This approach analyses how the decorative programmes were intrinsic to mendicant religious space and their importance in promoting their ideologies and garnering support. Wherever the medieval decoration survives, it soon becomes a critical collaboration between art historians, archaeologists and architectural historians, who all play a vital role in interpreting the mendicant visual imagery, which they often used as propaganda, especially in the second half of the 13th and in the 14th centuries. The Franciscans were passionate about painting, whereas the Dominicans admired sculptures.

Even though many archival sources tell us that many patrons left tombs and architectural elements such as portals, columns, and roof beams for the friars, we know that these objects rarely survived.

Studying these painted cycles and altarpieces can prove to be very beneficial to understanding the basis of architectural study. They often serve as documentation of stages of construction. More sources like inscriptions, texts, and testaments can be used to date building phases.

Friaries within the cities

As the Mendicant friaries gained significant relevance and importance, they became an integral part of society. Their reception depended on the city’s socio-economic status and the ideologies of fellow clergymen. Hence, it is paramount to recognise that friars’ buildings and convents responded in distinctive ways to the ever-changing external and internal circumstances due to their close connections to lay communities. Friars were particularly responsive (and vulnerable) to these social, political, and economic changes.

In order to associate themselves with the established communities, the mendicant’s approach varied depending on the social, religious, and topographical situation. They were well aware of the influence their friaries held, so their “mendicant identity” was of great importance.

Moreover, even though the friaries received hefty patronages, they were required to display visible signs of apostolic poverty. After the mid 13th century, the papacy’s affirmation of these new orders further aided in the promotion of a new attitude. This had repercussions in numerous regions across Europe. For example, in eastern Europe, there was the widespread adoption of ashlar masonry, as they were now associated with mendicant buildings that were part of permanent structures like the town halls. The friars displayed immense quantitative and qualitative knowledge and mastered the building trade, painting, glassmaking, and construction.

Towards the end of the 13th century, mendicant communities consisted of both men and women from local families. This meant that the convents were central and well mixed in with the local socio-political situations, and this would often lead to a rivalry with their apostolic poverty ideology.

The debate over the actual apostolic poverty is significant when analysing mendicant architectural features. Saint Bonaventure provided justifications for the large complexes of the Franciscans and why they were a necessity. As the mendicants grew and started flourishing, it soon became a challenge to find enough space to accommodate the new orders. Many of these were being “conventualised” in a sense, they started adopting similar architectural principles for their monasteries like refectories, dormitories, and cloisters.

The norms of monastic planning of the mendicant space started occurring in the Dominican orders around the 1220s. This order was usually more precise and deliberate in executing the constructions of their buildings. Conclusively, the adoption of the monastic model of architecture became advantageous as it proved to be efficient because of its arrangement around densely packed neighbourhoods.

The entire process of “conventualisation” was a concept that had practical advantages. It showed the shift from the strict norms of apostolic poverty towards progressive large-scale projects that involved the friaries serving as the nucleus of society due to their strategic positions and how they communicated with the people. These complex and extensive enterprises that operated in dense urban environments became one of the most important institutions in cities.

Socio-Economic Aspects

Historians, Nicole Bériou and Jacques Chiffoleau, examine the important aspects of the mendicant economy and reasons for minimal information about their finances during their inception. They emphasise how these friars managed to get funded for their churches and convents, which, over the years, became substantial and more expensive.

Additionally, Volti focuses on the social impact of the mendicants in northern France and the Flander region. Public preaching and the role mendicants played in supporting local clergy, merchants, businessmen, and politicians has been analysed and she further concludes the importance of burial traditions as well.

The societal practices of the mendicants revolved around preaching. Even though outdoor preaching was an established ideal, it became more universal, especially in Italy, where they created “preaching piazzas”. When interior preaching flourished, mendicants constructed supplemental pulpits inside their churches, many of which were portable. Hence, they were rolled in and out depending on the weather or the occasion.

The Dominicans started practicing integrating the laymen within their churches rather than going through the practice of preaching outdoors and in other churches. This increased their financial expenses, but it revolutionised communication between the clergymen and the laymen. Visitations to the homes of the poor and the destitute were highly effective and emotionally bound the mendicants to the residents.

This impact critically challenged the secular clergymen. The symbiotic relationship turned hostile and competition amongst them became common. The parish and the cathedral found themselves at odds with the mendicants on many major issues, including rights to the sacraments and the right to preach.

Ergo, dubious activities, along with unfavourable financial transactions, were practiced. Inquisitors would often abuse their power and influence the official records. (examples of this are practices at Santa Croce in Florence and Sant’Antonio in Padua) Santa Croce boasted more than 30 rooms and a massive prison as well. After the 1300s, courtrooms, office spaces, and prisons were constructed and a large administrative structure was established. Similar transformations reformed the friaries into huge and efficient administrative centres. Therefore, it was not surprising that many funds and properties were misused in order to benefit the institutions.

- Irish Artists: The Duality of Harry Clarke

- Ireland’s Historical Influence in South America

- Restitution and Repatriation: Art and Culture in 2021

Conclusion

Critically examining and analysing the history of the mendicants remains complex. However, with the research of scholars like Panayota Volti and Frithjof Schwartz, the subject has been re-examined and revisited.

The ethical conundrum that can be scrutinised provides an interesting look into their rapid transformation: (the early years and rise of mendicants) wherein they can be observed renouncing all materialistic objects, tithes, and any form of income.

There is indeed an argument to be made that similar patterns have been followed by most religious establishments, however, the reliance on the complete generosity of others was particularly unique, as alms and donations were critical for their survival. They relied on others for food, clothing, and shelter and it was only after 1250 that they were guarded by wealthy patrons.

Thus, the mendicant architecture remains a complex synthesis of socio-economic and theological approaches. This, in turn, inspired conflict within different established factions of the public, but it was eventually successful in transforming the surrounding topographical areas. The very relationship friaries formed with the laymen assisted them with establishing trust in a social, political, and economic context. The evolution and establishment of these convents can be looked at as a part of a relationship between the institutions that exist within a city. The history, in terms of architecture and its evolution, needs to be seen as the end product due to the evolving and successive projects. Whether it’s the text, photograph, or floor plans, they are all part of the production process.

The study of mendicant architecture is a very vast, vigorous, but rewarding field. The closeness of these friars to the process of social, religious, and institutional change is something that catches our eyes now. Approaches that hit both macro and micro levels offer new and exciting avenues towards an understanding of how these sacred spaces came to be.