The 8 Irish Pagan Festivals: Comprehensive guide to paganism

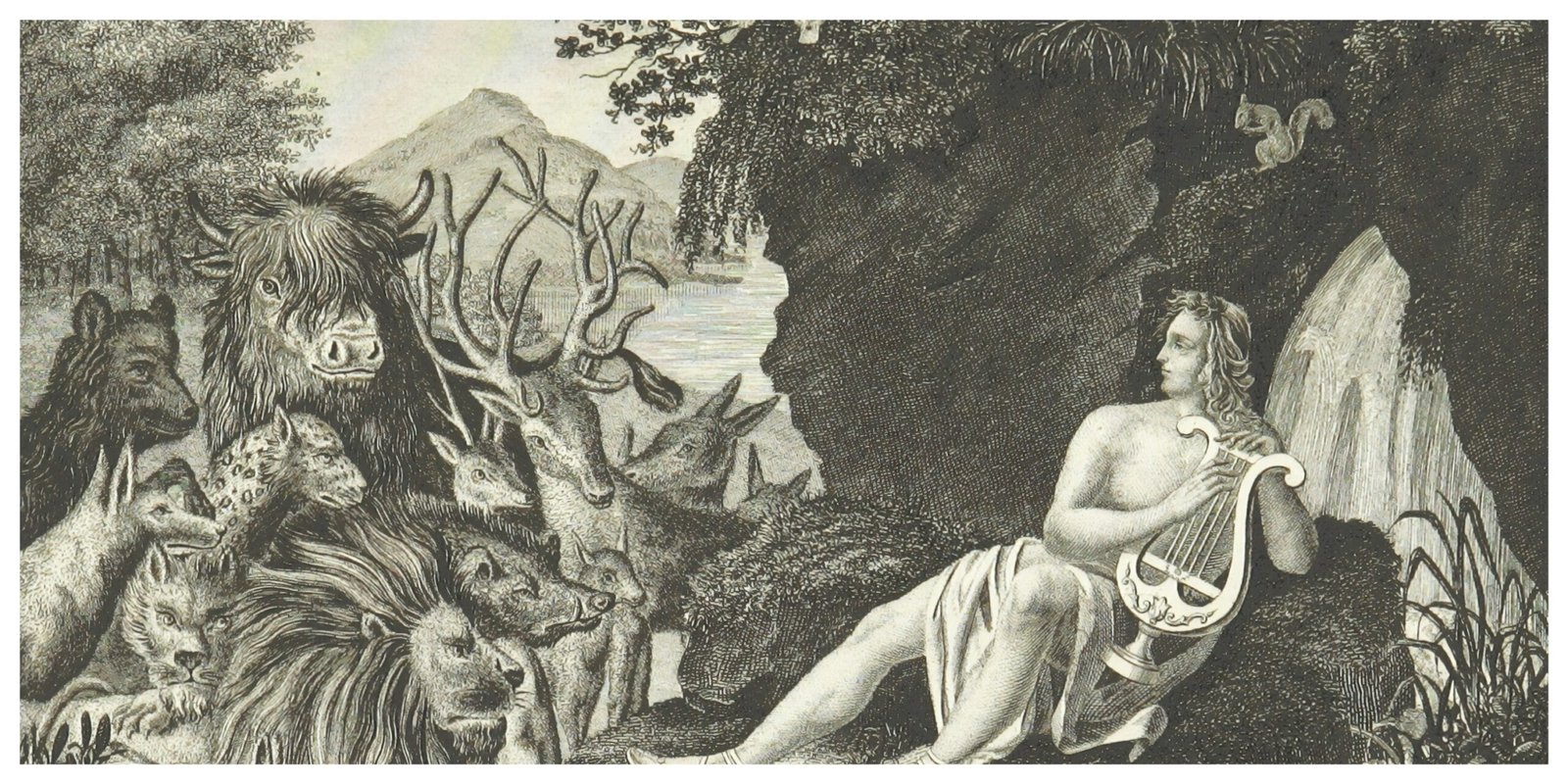

For centuries in pre Christian Ireland the pagan Irish calendar was divided into eight polytheistic pagan festivals occurring about every six or seven weeks throughout the year. The ancient Celts were polytheistic people and considered these times of utmost importance. They used them to mark the changing seasons and honour their Gods and Goddesses. These holidays were focused on spiritual aspects surrounding rebirth, fertility, the changing of the seasons and other natural events. This was due to the deep reliance and connection the pagan Irish people had to the natural world.

As Christianity took root in Ireland, many pagan festivals were reinterpreted or absorbed into the Christian calendar. Traditions like bonfires, feasting, and seasonal offerings were preserved, often under new names and meanings. Today, a growing Pagan revival, including Irish Paganism, celebrates the eightfold Wheel of the Year, marking solstices, equinoxes, and the four Celtic pagan festivals Imbolc, Bealtaine, Lúnasa, and Samhain. Alongside these solar festivals, ancient Irish spirituality also followed the lunar cycles, using the phases of the moon for rituals, planting, and divination.

Imbolc: A Celebration of the Coming Spring

Celebrated annually on February 1st, Imbolc marks the halfway point between the Winter Solstice and the Spring Equinox. This ancient Celtic pagan festival honours the return of longer days and the first signs of spring. Traditionally seen as a time of renewal, fertility, and new beginnings, Imbolc symbolises the land’s gradual awakening after winter.

The word Imbolc comes from the Old Irish i mBolg, meaning “in the belly,” referencing the pregnancy of livestock and the natural cycles of life. It’s also linked to early spring lactation and it is argued amongst scholars but some suggest it may relate to the idea of cleansing or ‘spring cleaning’ after the dark season.

Imbolc was later incorporated into Christian tradition as St. Brigid’s Day, honouring Ireland’s only female patron saint. Many scholars believe St. Brigid’s story was inspired by the Celtic goddess Brigid, a powerful figure associated with fertility, healing, and poetry

On Imbolc Eve, it was believed that Brigid would visit homes. Families prepared by setting out clothing or blankets to receive her blessing, sharing a special meal, and making offerings to the land, such as milk or porridge. Today, Imbolc is still observed through candle lighting, rituals of renewal, and a growing appreciation for its ancient roots.

Cónocht an Earraigh: The Bringing of the Spring Equinox

Each year between March 20th and 22nd, Cónocht and Earraigh the Spring Equinox marks a moment of perfect balance between light and darkness. For ancient Irish communities, this turning point symbolised rebirth, fertility, and a connection to An Saol Eile (the Otherworld. Though specific Celtic rituals tied to the equinox are not well documented, its symbolism of renewal runs deep in Irish spiritual heritage. The equinox aligns with the land’s slow awakening, a time to sow seeds both literal and metaphorical and welcome the brighter half of the year.

The Spring Equinox also resonates with the theme of sovereignty of the land. This is a key concept in Irish mythology where the health of the land is tied to just leadership and the people’s right relationship with nature. Celebrating this pagan festival was a way to reaffirm communal values and align oneself with the cycles of the earth, rather than stand apart from them. While the Spring Equinox doesn’t have the same depth of mythology as Imbolc or Samhain, its power comes from this subtle equilibrium and its message of hope and forward movement.

Bealtaine: The Fire of Summer’s Dawn

Bealtaine (May 1st) marks the vibrant turning point between spring and summer in the Celtic calendar. As one of the four great Fire Pagan Festivals of ancient Ireland, it celebrates the return of warmth, fertility, and life in full bloom. Traditionally, communities lit twin bonfires for purification and protection, driving cattle between them to safeguard their health for the season ahead. People also passed through the smoke for blessings of vitality, while homes were decorated with yellow May flowers to ward off ill fortune.

Bealtaine honoured the abundance of nature—fields ready for planting, animals heavy with young. It was also a liminal time, when the veil between worlds thinned and the Sí (fairy folk) were said to roam more freely either bringing blessings or interfering with the human realm. Offerings were left at doorways to appease these spirits and invite good fortune. Though later absorbed and reshaped by Christian traditions, many Bealtaine customs—like May Day flower rituals and festive fires—persisted in Irish folk culture, preserving the pagan festival’s core message: the triumph of light, life, and seasonal renewal.

The Summer Solstice: Grianstad an tSamhraidh

In modern Irish, meaning “Mid Summer, the longest day”, typically falls around 20th-21st June. This solar festival marks the longest day and shortest night of the year, celebrating the peak of the sun’s power. Although “Litha” is a name sometimes used, it is a Neo-Pagan term without a place in native Irish Paganism. Ancient Celts traditionally celebrated this time with bonfires and ceremonial dancing, viewing the fire as symbolising the sun’s power, protection, and purification.

Christian influence gradually shifted the tradition of bonfires from the Summer Solstice to St. John’s Eve, observed on June 23rd. This date, closely aligned with the Solstice, was appropriated by the Church to honor St. John the Baptist, overlaying pre-Christian fire customs with new religious meaning. In many rural Irish communities, the custom of lighting large communal fires, once meant to honor the sun at its peak and ensure fertility and protection for the crops and people, persisted under a Christian guise. These fires, often accompanied by music, dancing, and ritual practices like jumping through flames or carrying embers around fields, retain echoes of their Pagan past

Lúnasa: Honouring the First Fruits and the Labour of the Land

Lúnasa (August 1st), also known as Lughnasadh, marks the start of the harvest season in the Celtic calendar. Rooted in gratitude and resilience, it celebrates the first fruits of the land, the labour of the community, and the spiritual bond between people and nature. Named after the god Lugh, a figure of skill, light, and leadership, the festival was founded in memory of his foster mother Tailtiu, who died after clearing Ireland’s fields for agriculture. Her story reminds us that sustenance often requires sacrifice, and Lúnasa honours both that cost and the rewards it brings.

Historically, Lúnasa was observed through communal gatherings, featuring athletic contests, matchmaking, feasting, and large seasonal fairs such as Óenach Tailten in County Meath. These events were deeply spiritual, strengthening tribal alliances and celebrating the land’s abundance. The first harvest of grains, berries, and vegetables was offered to the gods and shared in community feasts. Today, modern Irish Pagans may bake bread, gather wild foods, or hike to sacred sites like Slieve Gullion or Croagh Patrick, connecting physically and spiritually to the ancestral land.

Lúnasa also marks a turning point in the Celtic year, the first of three harvest festivals, followed by the Autumn Equinox and Samhain. It’s a time of reflection and preparation, acknowledging the impermanence of abundance and the value of hard work. As the light begins to wane, Lúnasa invites us to honour nature’s cycles, live in gratitude, and embrace the balance

Autumn Equinox Cónocht an Fhómhair: The Turning of the Light

Autumn Equinox or Cónocht an Fhómhair (Late September) marks a moment of perfect balance between day and night, light and dark. In Irish tradition, this turning point is a time of harvest, gratitude, and transition, as the final light of summer fades and the darker half of the year begins. Known as Cónocht an Fhómhair, meaning “the equinox of autumn”.

Though less prominently recorded in early Celtic mythology than other pagan festivals, the Autumn Equinox resonates through seasonal rhythms from the last harvests in the fields to the changing colours of the trees. Traditionally, this was a time of preserving food, giving thanks, and readying the home and heart for winter. It’s also a time of spiritual balance, encouraging you to pause, appreciate life’s cycles, and honour both gain and letting go.

Today, Irish Pagan and nature-based communities mark this day with seasonal foods, small rituals, and offerings to the land. Activities like baking, blackberry picking, and communal meals reflect age-old themes of gratitude and humans’ connection to the land. While the festival is sometimes called Mabon in broader Neo-Pagan circles, this term doesn’t stem from Irish heritage. The Irish word Fómhar, meaning autumn or harvest, holds deeper cultural authenticity.

As with many Celtic pagan festivals, the Autumn Equinox was later Christianised—reflected in Michaelmas (St. Michael’s Day) on September 29th. Celebrated as a time of reckoning, thanksgiving, and honouring divine protection, Michaelmas echoes earlier traditions of marking seasonal change. Still, Cónocht an Fhómhair remains a powerful moment for balance, reflection, and reconnecting with nature’s cycles.

Samhain: The Death of Summer and the Thin Veil Between Worlds

Samhain is the End of Harvest, Beginning of Darkness (October 31st) stands as one of the most ancient and powerful festivals in the Irish Pagan calendar. Pronounced sow-in, Samhain marks summer’s end, the final harvest, and the transition into the dark half of the year. Often considered the Celtic New Year, this is a time of profound change, where death and rebirth, ending and beginning, exist side by side.

The word Samhain likely comes from samfuin, meaning “summer’s end,” and it remains the Irish name for November anchoring the pagan festival in both ancient tradition and modern language. Samhain is a liminal time, when the veil between worlds is thinnest. The spirits of the dead, the Aos Sí (fairy folk), and ancestors were believed to walk freely, and the síde (fairy mounds) were said to open, allowing passage between realms.

This spiritual openness made Samhain a time of reverence and caution. Offerings of food and drink were placed at doorways, on ancestral altars, or near natural features to appease and honour these beings. Messages to departed loved ones were written and burned in ritual fire, and protective charms like the parshell (similar to Brigid’s cross) were renewed for winter safety. The final fruits and grains were often displayed in thanks, blending gratitude with mourning.

On a practical level, Samhain was essential for seasonal survival. It marked the final harvest, the slaughter of livestock, and the beginning of long-term food storage. Ritual bonfires, originally “bone fires”, were lit on sacred hills such as Tlachtga and Tara, offering communal purification and protection. People would pass between the fires for blessings, echoing ancient customs of renewal.

Samhain also gave rise to mumming and guising, where people donned costumes to avoid or confuse spirits. This eventually evolved into modern Halloween traditions, including trick-or-treating, though the roots remain deeply Pagan. The masks, the laughter, and the play all carried spiritual weight, acts of defiance, honour, and connection in the face of encroaching darkness.

With Christianity’s arrival, Samhain was reimagined as All Saints’ Day (Nov 1st) and All Souls’ Day (Nov 2nd). These holy days preserved the practice of honouring the dead, though under new religious framing. Yet many pagan customs quietly persisted, woven into rural life and seasonal observance.

Today, Samhain is still a time of ritual, remembrance, and release. Whether lighting a candle for an ancestor, gathering with community, or walking alone under lengthening shadows, this festival reminds you to pause, reflect, and embrace the turning of the wheel. It is a sacred threshold between light and dark, life and death, memory and becoming.

The Winter Solstice: Grianstad an Gheimhridh, The Sun’s Return

The Winter Solstice, known in Irish as Grianstad an Gheimhridh, marks the shortest day and longest night of the year. Falling around December 21st, it stands as a sacred still point in the wheel of the year, a threshold between darkness and light, death and renewal. Though the earth lies dormant and the cold is deep, this is a time of quiet promise: the sun will rise again, and from this day forward, the light begins to grow.

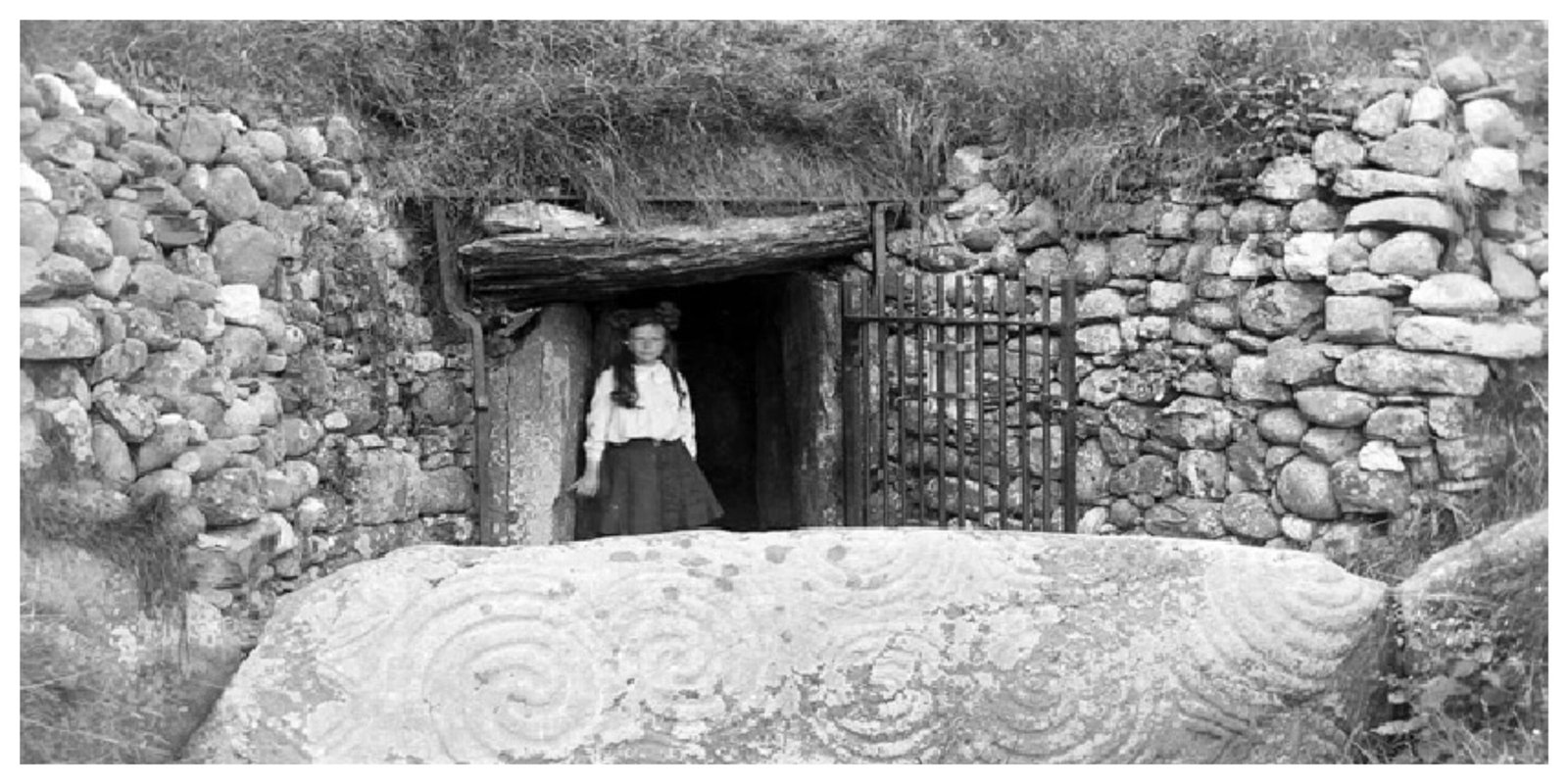

The Irish name reflects its cosmic meaning grian (sun) and stad (stop or standstill) evoking the stillness of the solstice moment. In ancient Ireland, this event was deeply observed, and its significance is dramatically enshrined at Newgrange (Brú na Bóinne), the 5,000-year-old Neolithic passage tomb in County Meath. Each year at sunrise on the solstice, a narrow beam of light enters the passage and illuminates the inner chamber, filling the darkness with sunlight. This precise solar alignment suggests that midwinter was a moment of cosmic connection, spiritual rebirth, and awe.

Fire and light have always played a vital role in midwinter rituals. Bonfires and altars with many candles were lit to welcome back the returning sun, a tradition that eventually evolved into the burning of the Yule log. This glowing symbol of warmth and continuity was a physical and spiritual anchor during the darkest time of year.

In Celtic myth, the Winter Solstice also marks the turning of the solar tide, the symbolic battle between the Holly King, ruler of the waning year, and the Oak King, who now triumphs as the days lengthen once more. This narrative reinforces the cyclical rhythms of nature and the enduring belief that after darkness, there is always light.

Though early Christianity overlaid this moment with new religious meaning celebrating the birth of Christ as the light of the world many solstice traditions persisted. Evergreen decorations, feasting, gift-giving, and communal gatherings all echo the older Pagan customs that honoured the return of the sun and the life it brings.

Today, Irish Pagans and nature-based practitioners continue to mark the solstice with sunrise vigils, candle rituals, storytelling, and reflection. Some make pilgrimages to ancient sites like Newgrange, while others honour the moment simply by lighting a fire, sharing a quiet meal, or pausing to feel the stillness.

Wow … I had no idea how paganism impacts our cultural traditions!

Wow. That’s really interesting & a great piece of writing!

Very interesting! Going to pass on to some friends who celebrate these festivals 🙂

So very interesting. Very informative and great to know this about our culture.

Such a well written piece, full of insight and interesting detail, an education for me.