The history of graffiti

Graffiti and street art has been created since the dawn of civilisation. From cave paintings to wall murals, graffiti has always been part of our lives. Opinions on whether it is art or vandalism have been divided for almost as long. Here is an overview on the origins and evolution of graffiti and how it’s seen by society.

The origin of graffiti

Human civilization has been creating graffiti since its beginning. Graffiti is the word for writing, drawing, or painting on walls or surfaces of a structure. Just as our language systems evolved from prehistoric forms of writing such as Egyptian hieroglyphs, our practice of graffiti begins here too. The Lascaux cave paintings in France, one of the oldest examples of cave paintings, are considered an early form of graffiti, as handprints and large paintings of animals are found throughout the cave. The Knowth passage tomb near Newgrange contains graffiti that dates from 700-750BCE, and the Tikal site in Guatemala contains ancient Mayan graffiti. Arabic graffiti has also been found along the walls of the Garni Temple, which is thought to date back to the 9th-10th centuries CE.

The word graffiti is the plural of “graffito,” derived from the Italian word graffio, which means “a scratch.” Markings etched, scratched or carved into walls can be found in sites around the world and throughout time..

Early graffiti

As societies and civilisations progressed, graffiti was drawn in places that we would expect to find graffiti today. Ancient Romans carved graffiti on walls and monuments, even in the Catacombs of Rome or at Pompeii. It’s fascinating to see that the type of graffiti written even back this far is remarkably similar in context and sentiment as the graffiti we see today.

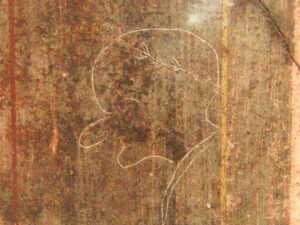

The eruption of Vesuvius preserved the graffiti in Pompeii and makes it a repository for some of the most well-known and well-preserved examples of ancient graffiti. Latin curses, declarations of love, insults, alphabets, political slogans, and famous literary quotes can all be found on the walls in Pompeii. One example is a man with a comically long nose that was carved on the side of a mansion (pictured above). The man appears to be wearing a wreath on his head, so it appears that this piece of graffiti is aimed at slandering a prominent figure.

The basilica is full of lewd and crude graffiti, such as “Chie, I hope your haemorrhoids rub together so much that they hurt worse than when they ever have before.” Gladiator barracks were also covered with messages like “Celadus the Thracier makes the girls moan! (Suspirium puellarum Celadus thraex!)” Another early form of graffiti was found in the Hagia Sophia mosque in Istanbul. A Viking mercenary wrote “Halvdan was here.” As you can see, the scrawls you see on walls today are no more elegant or creative than what was written in antiquity.

Evolution

In the 1920s there was a movement of Mexican street art founded by Diego Rivera, Clemente Orozco and David Siqueiros. Their political murals created an impact that swept throughout Latin America and reached the United States.David Alfaro Siquerios’ mural America Tropicál was painted in 1932 in Los Angeles and depicts a crucified Chicano attacked by an eagle that represents America. It was subsequently painted over, but later restored.

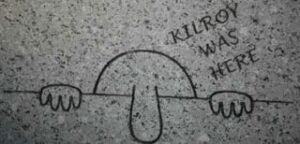

During World War II, allied soldiers would write “Kilroy was here,” along with a simple sketch of a bald figure with a large nose peeking over a ledge. It was so popular, it became a meme before the term ‘meme’ had even been coined. Variations such as Foo in Australia and Chad in Britain popped up. The idea behind it was to create a sense of connection and comfort, as seeing this graffiti indicates that one of their own has been here before. Some say that Hitler was worried that Kilroy was some sort of codeword, or was a spy, while others say he was worried about the joy and motivation these drawings inspired in Allied troops.

The “Kilroy was here” phase wound down in the 1950s, but picked back up when the US became involved in the conflict in Vietnam in the 1960s. The use of graffiti to create a sense of connection and community is one that pervades.

Graffiti has been co-opted by groups throughout history, such as gangs or other cultural or sub-culture groups. The “urban” style of graffiti that is common today seems to have evolved in Philadelphia in the early 1960s, and by the late 1960s it had reached New York. Train cars have been a hotspot for graffiti for as long as we’ve had trains, and subway trains made it easier for people to spread and consume graffiti. Artists were commonly called “writers” or “taggers” (people who write “tags,” either a nickname or stylised signatures). Graffiti became popular with teenagers and is associated with hip hop and is also considered one of the four elements of the subculture (along with emceeing, DJing, and B-Boying).

The 1983 documentary Style Wars, directed by Tony Silver, is still considered the best film representation of what was going on within the young hip-hop culture of the early 1980s, and what role graffiti played within this culture. The film features graffiti artists such as Skeme, Dondi, MinOne, and ZEPHYR, and incorporates early break-dancing groups such as Rock Steady Crew and a rap soundtrack to reinforce the role of graffiti as a form of expression in hip hop culture. The film frames graffiti as a way for youths and minority cultures to reclaim the city (an attitude not so surprising in Regan-era America). The artists interviewed for the film were shown having gatherings and sketching designs in notebooks. Interviews with politicians are pitched against them, insisting that they are vandals and criminals.

From train cars to gallery walls

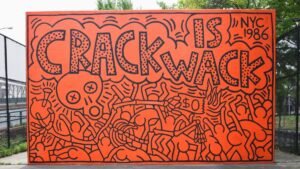

Street art started to be appreciated as art in its own right in the 1980s. Jean-Michel Basquiat was creating street art in the 1970s before he became a respected artist in the 1980s. Keith Harring also made his start on the streets before becoming an internationally renowned artist. Banksy is probably the most (in)famous graffiti artist, with his works being sold for over £100,000. Institutions like London’s Tate art museum have celebrated street art and welcomed it as a commercial artform. This however isn’t a transition without complications — the inclusion of select artists and art style into the institution of art creates elitism and a shift in the original aim of street art. Also, these highbrow galleries that show graffiti would never allow their own buildings to be ‘tagged,’ which indicates the complexity of the perception of street art.

Art or crime?

The debate over whetherstreet art is legitimate art or vandalism has raged on for decades, with no clear right or wrong answer. Ed Koch, who was Mayor of New York at the time Style Wars was filmed, referred to graffiti as a “quality of life crime” and likened it to theft, claiming that it is “destroying our lifestyle and [making it] difficult to enjoy life.” As an anti-graffiti measure, it’s actually illegal in many US states for a person under 18 to purchase a can of spray paint or permanent marker, or to have these items while on public property. Michael Bloomberg, Mayor of New York from 2002-2013, actually tried to get this bumped up to the age of 21. The debate is positioned as a clash between the wealthy property-owners and law-makers, and the disenfranchised youth and minorities that are trying to reclaim cities from advertisers and add vibrancy to the city.

The crux of the issue is with ownership: painting on a building/property you don’t own makes it vandalism and a crime, no matter how beautiful the piece is or what message it’s sending. We’ve had this issue recently in Ireland when the ‘Repeal the 8th’ mural was painted over. This was met with outrage, particularly since the mural was advocating for women’s ownership of their own bodies. Collectives such as Subset are actively trying to change the country’s attitude towards graffiti and advocate for a change in the legal process and requirements for creating street art.

What do you think? Should the laws around graffiti be relaxed? Or do you think it’s vandalism? Let us know in the comments!