10 Irish Mythological Creatures: History Through Myths

Knowledge of Irish mythological creatures

If there is one thing that Ireland is known for (besides alcohol) it’s our ability to produce incredible writers, poets, and musicians. People like W.B Yeates, James Joyce, Oscar Wilde and Bram Stoker are part of the reason why Ireland has earned the title: The Land of Saints and Scholars.

The ability to tell ‘tall tales’ isn’t a gift solely bestowed on artists like this however. Long before the Christianisation of the island of Ireland, the people had created weird and wonderful tales to help make sense of the world around them.

Obviously, mythology isn’t in any way unique to Ireland. In fact, the mythology most people are aware of is that of the ancient Greeks and the Vikings. These stories seem to be forever growing in popularity through their representation in movies, literature, television, and video games, and there are few among us who aren’t at least aware of the stories of Hercules or Thor.

Why then, does Celtic mythology not get the same attention? It is likely because other civilisations, the Greeks in particular, actually wrote many of these myths down, allowing them to survive the test of time. Unfortunately, the Celts didn’t do this. They relied instead on oral tradition, passing stories down to the next generations, allowing the tales to become less consistent and to, eventually, die out completely.

Also, the Greek and Norse people organised their Gods into complex pantheons while the Celts didn’t, and hence the Gods and goddesses were more local, and therefore less consistent.

Whatever the reasons, lovers of mythology from around the world have missed out on some truly fascinating stories based around Irish and Celtic mythology. Particularly, the cast of creatures that feature in them.

Some possess the whimsical nature that is expected of Irish myths, but others are as dark, terrifying, and gruesome as any creatures you’ve seen in modern horror movies or video games.

The Banshee

“All they knew of religion was the Bean Sidhe, the banshee, who came to wail at the walls of a house where death soon would be.”

-Neil Gaiman

One of the most well known Irish mythological creatures, both in Ireland and abroad, the banshee is one of the most terrifying creatures conjured up by the twisted mind of mankind.

Appearance

The banshee appears in a few different forms, she can appear as a beautiful, ethereal young woman, or a stately matron type, but she is most commonly depicted as a crouching old hag with a hideous wrinkled face. She is also said to be the ghost of a woman who died in childbirth, and sometimes appears as a crow, stoat, hare, or weasel.

Whatever form she is witnessed in, she usually has long silver hair that she is brushing with a comb. Because of this, there is a superstition in Ireland that if you find a comb lying in the woods, you shouldn’t pick it up or you’ll be kidnapped and taken away by fairies. Although most people don’t touch mouldy forest combs for hygiene reasons.

She is said to wear either a grey hooded cloak or the grave robe of the dead, and her eyes are perpetually red from crying.

Many believe that she can take any of the above forms, and change between them as she pleases.

Behaviour

Any child who grew up in Ireland has heard the stories of the banshee, who screams and wails mournfully outside of a house if a family member is about to die.

Aside from that, she isn’t known to interact with humans very much, never getting any more physical than scratching at the windows and doors of the unfortunate family. Which when you think about it, is beyond horrifying.

The sound of the screams is also a matter for debate, with people from different parts of Ireland claiming different screams. In Leinster, the scream is said to be so shrill that it shatters glass, in the north, it sounds like two boards being slammed together, and in Kerry, it’s a low pleasant singing.

Regardless of the sound, she is sometimes heard screaming for a few days before the death actually occurs, and sometimes just once.

Aside from being an omen of death, the banshee would also cry at the crowning of a true king, a famous example occurring at the crowning of Brian Boru.

There are also stories that state that only descendants of legendary king Brian Boru will hear the banshee’s cry. And another stating that only five specific families are targeted by the banshee: The O’Briens, O’Neills, O’Connors, O’Gradys, and Kavanaghs.

Unlucky lads.

Origins

The idea behind the banshee comes from medieval times, when women called keeners were paid to come to funerals and sing sad songs called caoineadh (the Irish word for ‘crying’). As ridiculous as this sounds, families would actually pay a lot of money for a talented keener.

It is said the most wealthy and powerful families would hire a Bean Sidhe or ‘fairy woman’ to come and keen at the grave, since as we all know, fairies are much better singers than humans.

The myth was built upon by the fact that, in a true stereotypical Irish fashion, the keeners would be paid only in alcohol, and would end up as alcoholic old women who would eventually get banished from their communities as a result.

As for the scream, many believe it likely came from people hearing the screech of a barn owl late at night.

Legends

Again, since Irish mythological stories were mostly passed on orally, there are not a lot of ‘confirmed’ encounters with a banshee. But here are some famous ones.

In 1437, a woman claiming to be a seer approached King James I of Scotland and told him he would be murdered at the Instigation of the Earl of Atholl.

Spoiler: He was.

Another, more recent case was in 1801 when Robert Cuninghame, the Commander in Chief to the British Forces in Ireland, dubbed the 1st Baron of Rossmore, invited some people to his house in County Wicklow after a party in Dublin castle. During the night, some guests reported hearing a ‘deep, heavy, throbbing sigh’ followed by a low voice saying ‘Rossmore’ repeatedly. The next morning the guests learned that their host had died suddenly during the night.

Leprechauns

“… quite a beau in his dress, notwithstanding, for he wears a red square-cut coat, richly laced with gold, and inexpressible of the same, cocked hat, shoes and buckles.”

-Samuel Lover

Probably the most famous Irish mythological creature, especially according to Americans, the leprechaun has become a somewhat involuntary symbol of Ireland.Usually depicted as friendly, whimsical little men, they are not quite as harmless in mythological stories.

Appearance

In pop culture, a leprechaun is a short old man with a red beard wearing a green suit and top hat, usually with pockets stuffed full of gold coins. Even though their appearance in mythology doesn’t stray too far from this, they originally were described as wearing red rather than green.

There are a number of clothing variations for these creatures, but they are mostly just different coloured jackets, socks, and pants, and sometimes wearing a leather apron.

Some describe leprechauns as carrying a sword which they use as a magic wand.

Behaviour

As mentioned above, leprechauns are not as full of whimsy in Irish mythology as they are in pop culture. But nor are they the absolute embodiment of evil as portrayed in 1993’s Leprechaun starring Warwick Davis and Jennifer Aniston.

Instead, leprechauns are more of a mix of the two, not being inherently good or evil. They instead are seen as tricksters, who will usually leave people alone. In fact their primary occupation is mending shoes.

They often possess a crock of gold, and if they are captured and threatened with violence will usually tell his captur where his gold is hidden. However, if you look away even for a second, they will disappear without a trace. As they are natural tricksters, they can distract you very easily.

The whole ‘end of the rainbow’ thing is unfortunately an Americanisation.

Origins

In mythology, leprechauns are said to be descendants of Tuatha de Danann, a mythical race who were driven underground by the Milesians (Celts), and live in fairy mounds dotted around the Irish countryside. They are also said to be the sons of an evil spirit.

In reality, the word leprechaun is derived from the Irish word leipreachán which means ‘pigmy’ or ‘sprite’.

Legends

The earliest known story involving a leprechaun is from a medieval tale called Adventure of Fergus son of Léti, where the king of Ulster falls asleep on a bench and wakes up to find himself being dragged towards the seas by two leprechauns.

He overpowers and captures the creatures and they agree to grant him three wishes to exchange for their release

Púca

“I’ll follow you. I’ll lead you about a round,

Through a bog, through bush, through brake, through brier.

Sometime a horse I’ll be, sometime a hound,

A hog, a headless bear, sometime a fire,

And neigh, and bark, and grunt, and roar, and burn,

Like horse, hound, hog, bear, fire, at every turn.”

-William Skakepeare, “Midsummer Night’s Dream”

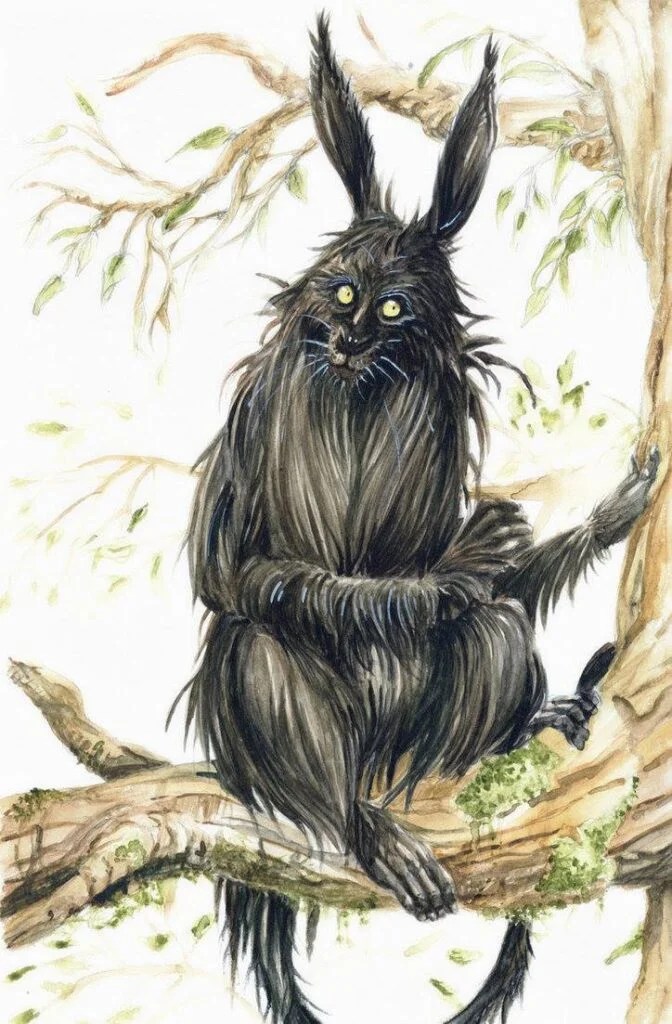

The Púca is present in the folklore of not only Ireand, but also Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany. So pretty much every Celtic region. The above quote was said by Shakespearian character Robin Goodfellow (aka Puck) who is considered by some to be inspired by the Celtic and Irish mythological creatures.

Appearance

The appearance of Púcai is hard to define, simply because they are shapeshifters. They often take on a human form with animal features, or will just take on the form of animals like a horse, cat, or rabbit. Some depictions of pucai describe them taking the shape of a goblin wearing a long black coat.

In Wexford, it is said to take on the form of an eagle, in Roscommon, it appears as a black goat, while in Laois, it takes on the form of a boogeyman character.

You get the picture, it’s a shapeshifter.

Behaviour

Like the leprechaun, Púcai are not really considered either good or evil, and are often seen as a trickster.

However, they do seem to enjoy human misery a lot more than the leprechaun does. Taking the shape of a large black horse and trampling crops during the night. If cows or chickens see the Púca they will be so traumatised that they will no longer be able to produce milk and eggs. Farmers would leave a portion of their crops for the Púca to take in order to appease the creature temporarily.

This tradition is still upheld by some farmers today, who leave a ‘Púca’s share’ in order to placate it.

On a Púca’s more peaceful side, they have also been known to appear to people who are just about to be involved in a serious accident or happen upon a malevolent spirit.

Finally, pucai have been known to play practical jokes on local people. Targeting drunks coming home late at night, enticing them onto their backs, and taking them on a wild ride before dumping them off in the early hours of the morning. This apparently accounts for those of use that have no recollection of what happened the night before.

Personally, I feel that being run ragged through the countryside on the back of a huge horse is a preferable story to puking your guts up in a nightclub toilet and falling asleep in a gutter.

Origins

‘Púca’ is the Irish word for ghost or spirit. While the Púca is most likely a creature of celtic mythology, there are some who believe that it originally comes from Norse myth, with all Scandinavian languages having similar words for an evil spirit.

The Púca has been referenced in the texts of several famous writers, including W.B Yeats, Brian O’Nolan, and of course, William Shakespeare.

Legends

Apparently, the only human to ever successfully ride a Púca was High King of Ireland Brian Boru. He controlled the magic of the creature by using a special bridle made using three hairs from the Púca’s tail. Thanks to his physical prowess, Brian stayed on the Púca’s back until it became exhausted and surrendered to him.

After his victory, Brain forced the Púca to make two promises: that it would no longer torment people and ruin their property, and that it would never again attack an Irishman unless he was drunk or had evil intent.

The Oilliphéists

Contrary to popular belief, not all Irish Mythological creatures are variations of fairies and ghosts. An exception being the Oilliphéists, otherwise known as Irish dragons.

Appearance

Even though these creatures have been called ‘Irish dragons’ they don’t seem to ever be described as the winged, fire-breathing, monsters we all know and love. Instead they are depicted as sea serpents.

The name Oilliphéist comes from the Irish word Oll meaning ‘great’ and péist meaning ‘worm’. So, Greatworm. Sounds better in Irish.

Behaviour

Oilliphéists are known to inhabit the lakes and rivers around Ireland, and there are many stories of them going toe to toe with Irish heroes. Including Fionn mac Cumhaill and the man himself, Saint Patrick. I guess sea serpents are sort of like snakes.

Legends

In Irish folklore, Caoránach is an Oilliphéist and is said to be the mother of all demons. One legend says that Fionn mac Cumhaill and the Fianna were asked to kill an old hag who lived near Loch Derg in Donegal. She was killed by an arrow and her body fell into the lake. When it was eventually recovered, they were warned not to break her thigh bone or it would release a dangerous monster.

A man named Conan broke the thigh bone anyway, and a small worm was released, and quickly grew into Caoránach who began to devour all the cattle in the region. Conan was (righly) blamed for this, and in a fit of fury he found Caoránach and killed her. Her blood dying the lake red, hence the name, Loch Derg (Dearg being the Irish for red).

A Christianised version of the story states that Saint Patrick was the one who killed Caoránach, Although some tales say he failed and that Caoránach lives in Loch Derg to this day.

Another legend states that the River Shannon was created when the Oilliphéists carved through Ireland to get to the Atlantic Ocean after the arrival of Saint Patrick.

Many people claim that these legends are the inspiration behind the Loch Ness Monster. Maybe Caoránach is Nessies Ma.

Abhartach

“Might not the legend of the vampire-king, coupled with the strong tradition of blood-drinking Irish chieftains and nobles recounted to him as a child by his Sligo-born mother and the Kerry maids who worked about his Dublin home, have eventually coalesced into the idea of Count Dracula?”

-Bob Curran

The Abhartach is known by many as The Irish Vampire due to his fondness for the red stuff. However this Derry-based tyrant was, in fact, a dwarf, and probably mythology’s most terrifying result of small-man syndrome.

Appearance

Abhartach is the Irish word for dwarf, which is what this creature was known as – and could be why he was so pissed off.

Obviously he was short in stature, but aside from that, not much is known of his appearance. Except that when he gained the powers that allowed him to wreak havoc on all of Ireland, he was ‘strangely changed’ in appearance, and had glowing green eyes that could be seen from far away, and a smell that stretched even farther.

Behaviour

Abhartach is said to have possessed magical abilities, and used them to take what he wanted from the people of the village of Slaghtaverty. Those who refused would be struck with blight or illness, crushed by stones, or simply found dead in their homes, faces twisted in pain.

He was also known to drink the blood of his victims and could only be killed using a sword made of yew and then buried upside down.

Origins

According to Bob Curran, a professor of Celtic history and folklore at the University of Ulster, the Abhartach is most likely the influence for Bram Stoker’s Dracula and not Vlad the Impaler.

He says that the real Dracula’s castle is located between Garvagh and Dungiven in Northern Ireland.

Legends

Growing up, Abhartach was bullied for his size, but managed to ingratiate himself to a local druid who knew a lot about various incantations and spells. One day, Abhartach and the druid went missing along with many scrolls and texts.

When he returned he took revenge on all who wronged him by taking whatever he wanted from them. The people of Slaghtaverty convinced a neighbouring chieftain to deal with Abhartach, some say that this was Fionn mac Cumhaill, and others say it was a man named Cathain.

Either way, the chieftain killed Abhartach and buried him standing up, according to their customs. The next day however, Abhartach returned more powerful than ever, this time demanding a bowl of blood from his victims.

Again, the chieftain killed and buried him, and again he returned more powerful than ever, this time spreading his terror over the whole of Ireland.

The chieftain consulted a druid who told him that he had to kill Abhartach with a sword made of yew and to bury him upside down. After this was done, Abhartach never returned.

The burial place of Abhartach is not lost, and is said to be under a hawthorn tree and some stones on a dolmen near the village of Slaghtaverty.

In 1997, an attempt was made to clear the land, but a brand new chainsaw malfunctioned three times when trying to cut down the tree. While trying to lift the stone, a steel chain snapped, cutting the hand of one of the workers allowing his blood to soak into the ground.

The Sluagh

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

“Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice:

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore-

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;-

‘Tis the wind and nothing more.”

-Edgar Aleen Poe, “The Raven”

Of all of the countless creatures that exist throughout all of the mythologies in the world, there are few creatures more terrifying more grotesque than creatures rejected by both heaven and hell, cursed to roam the earth forever, than the creatures known by names like the Underfolk, the Host of the Unforgiven Dead, the Wild Hunt, or in Ireland, the Sluagh.

Appearance

As with most Irish mythological creatures, the Sluagh’s appearance varies slightly from tale to tale. In some stories they are described as zombie-like creatures. Haggard and thin, with skin hanging off the bone. While in others, they are seen as bird-like, with long, leathery wings tucked close to their bodies like a weathered cape.

They have bony claws instead of hands and feet, spare strings of hair, and have sharp, crooked teeth poking out of their beak-like mouths.

Picture them as similar to the Ra’zac from the Eragon book series.

This is a far cry from their norse and slavic counterparts, the Wild Hunt, who are mostly described as ‘wraith-like’ soldiers on horseback, but in my opinion, these bird-like scavengers are far more terrifying.

Behaviour

Just like the Wild Hunt, the Sluagh are known to feed on the souls of anyone that crosses their path.

With their appearance being so obviously horrifying, they tend to skulk in the shadows and keep to the night skies. Sightings describe them as a flock of large ravens that further darken the night sky.

Similar to fictional characters like Bloody Mary and Candyman, the very utterance of the word Sluagh can call them to you. So if you’re tired of that soul weighing you down, give it a go. Another way that the Sluagh can be called to you is through the sheer hopelessness of one’s heart, and it’s said that those who die of a ‘broken heart’ are actually victims of the Sluagh.

They are known to fly in from the west and steal the souls of the dying before they can be given their last rites. To this day, many people lock the west-facing doors and windows of their houses to keep out the Sluagh.

Origins

The origins of the Sluagh stem from Ireland and Scotland over a thousand years ago. However, like the Puca, other cultures like Czech, German, Scandinavian, French, Polish, and Russian also have some version of the creatures that are popularly known as the Wild Hunt (mainly thanks to this).

Sluagh is the Irish word for host, and prior to the Christianisation of Ireland, they were considered to be ‘fae (faeries) gone amuck’ possessing no mercy, reason, or loyalty. After Saint Patick introduced God to the Irish people however, the Sluagh became a group of unforgiven, dead sinners.

Legends

A scholar named W.Y. Evans-Wentz travelled through Ireland, Scotland, and England from 1908 – 1910 collecting first hand experiences with faeries of all types and chronicling them in his book The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries.

One account collected from Barra in Scotland claimed that a young boy was taken by the Sluagh, had his soul extracted, and was dropped from a great height. His body was found in his back garden the next morning.

Bánánach and Bocánaigh

Bánánach, and their male counterparts, Bocánaigh are other Irish mythological creatures known to feed on death and misery. Ireland was a miserable place in the past to be fair, so I doubt they were ever too hungry. These creatures however, specifically thrived on warfare and violence.

Appearance

Bánánach are described as being screaming female demons or specters. Their name itself gives us some clues as to their appearance: bean or ban meaning wife or female, or, bán meaning white, fair or pale. So a suggested translation is ‘pale-faced woman’ seemingly being corpse-like.

Alternatively, Bocánaigh are not described as ‘pale-faced men’, instead they are often described as men with the heads of goats – the Irish word bocán meaning ‘male-goat’.

Both sexes however, are generally described as shrieking airborne demons.

Behaviour

Bánánach and Bocánaigh are known to fly over areas of combat, namely battlefields, hence their attraction to war and bloodshed. The Bocánaigh in particular, were said to cheer and roar at the carnage below.

Unlike other creatures on this list, they don’t seem to ever bother the living, but are more preoccupied with the dead. However, the Bánánach are said to have an interest in sex, and can be sexually promiscuous towrdas humans. I imagine people would stay away either way though. Depends what you’re into I suppose. Necrophiles apply within.

Origins

Comparisons have been made between Bánánach and the Scandinavian Valkyries due their appearance, sexual promiscuity, and fascination with warfare. However, it is not clear if one was influenced by the other or if it’s purely coincidental.

The Bocánaigh on the other hand, share more similarities with Germanic trolls and giants.

Legends

Ireland’s history of bloodshed likely influenced the myths of the Bocánaigh and Bánánach. From the numerous invasions by the Vikings and Normans, where demons were seen floating among the stormy weather, to the final battle of the 1798 rebellion against the English, where the rebels were massacred and buried at Shanmullagh hill in Longford.

The Irish rebellious spirit lived on, and so did these demons of war.

The Dullahan

“The entrance to C’Adder is guarded by a creature

Who rides a black unicorn, carrying his head in his hand,

His eyes watch all strangers, pilgrims of God

Who have been chased from their dwellings, robbed of their land.

The Dullahan rides his black unicorn all day and night

As Neir watches through terrified eyes,

His laughter she hears, trying to cover her ears,

Knowing, when he stops riding, a mortal will die.”

-Daniel McDonagh

This is one of the most famous mythical creatures out there due to its association with Halloween. The Dullahan has been made slightly more family friendly thanks to the replacement of a severed head with a super spooky pumpkin. But he originally was the terrifying Headless Horseman.

Appearance

Since the ‘Headless Horseman’ has been present in pop culture for quite some time, and the name is pretty self descriptive, it’s not hard to imagine what this creature would look like.

He is said to ride either on a black horse, or on a black carriage drawn by six horses. The carriage itself is said to be made of bones, tombstones, and coffins. In both depictions, the horses have flaming red eyes.

The Dullahan himself wears a long, black cloak and he holds his severed head high in the air to scan for his victims. His head is covered in rotten flesh, has the complexion of stale dough, and smells of mouldy cheese.

In his other hand he carries a whip made out of a human spine, which he uses to blind people.

His mouth is permanently twisted into a horrifying, ear-to-ear grin, and his eyes are wide and constantly darting back and forth. Still not as spooky as a pumpkin.

Behaviour

The Dullahan’s horses run with such ferocity that flames shoot from their nostrils and spark from their hooves. Whenever he stops, a human dies.

People who make eye contact with him are said to immediately be blinded either by their eyes being whipped out or by having a basin full of blood thrown in their eyes.

He can also speak, and when he says the name of his intended victim, their death is marked and they can no longer avoid it.

The Dullahan’s only weakness is said to be precious metals like gold, and superstitious families used to carry gold with them in order to scare the Dullahan’s horses away.

Origins

The Dullahan is actually thought to be the original depiction of the Headless Horseman, who has since appeared in many famous stories like The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and the stories of the Brothers Grimm. Variations of the Dullahan have appeared as far away as Japan.

The Dullaghan also appears in Dutch mythology having almost identical features and behaviour. In German folklore, there is a Headless Horseman who blows a horn to warn hunters not to ride, or death will befall them.

Modern fantasy stories and video games also depict the Dullahan as an evil character. So this Irish mythological creature will be around for quite some time.

Legends

The Dullagan is said to be the physical manifestation of Crom Dubh – the Celtic God of fertility. King Tighermas, king of Ireland, was a worshiper of Crom Dubh, and provided the deity with a yearly human sacrifice. Crom Dubh’s preferred sacrifice was (unsurprisingly) decapitation. Can you see where this is going?

When Christianity came to Ireland, these sacrificial rituals were condemned and eventually banned altogether.

And so, Crom Dubh himself appeared in Ireland in the form of the Dullahan, so he could search for these sacrifices himself.

Fear Gorta

This creature has more of a depressing historical backstory than others on this list. Fear Gorta literally translates into Man of Hunger or Man of Famine, and what’s more depressing than the famine?

Appearance

The Fear Gorta, like some variations of the Sluagh, takes on the appearance of a zombie-type character. A walking corpse, with deathly grey skin, protruding bones, and rotten flesh.

It is so thin and weak that it cannot even hold a cup of alms. Its hair and beard are long, grey and matted.

Its nails are long and dirty, and the flesh on its cheeks have completely rotted off, and it is dressed in rags.

Depressingly enough, this is probably not too far off the appearance of the Irish people during the Great Famine.

Behaviour

The Fear Gorta is known to wander the countryside during famine times and ask those it sees for alms (money or food for the poor). If someone gives the Fear Gorta food, they will be blessed with prosperity in return for their generosity. But if they refuse, the Fear Gorta curses them with eternal hunger, poverty, and bad luck.

Even though the Fear Gorta was not known to attack people it has been known to do so if provoked, or if it isn’t given what it asks for.

Origins

Not much is known for certain about where the myth of the Fear Gorta came from, but the most likely answer is that people may have mistaken desperate famine victims begging for food for this creature. These people may then have equated any misfortune that befell them (there was plenty to go around back then) as the curse of the Fear Gorta.

Legends

Another variation of the Fear Gorta describes it not as a man, but as a cursed patch of grass or ‘Hungry Grass’ that has grown over a mass grave of famine victims. Anyone who walks over it is cursed with a hunger that, no matter how much you eat, will not be satisfied, leading to madness and death.

One legend about the ‘Hungry Grass’ is that it is actually the site of importance to the fairy realm, and the fairies used their magic to curse the land to keep humans away.

Some say that the destruction, be it accidental or otherwise, of these sacred grounds has led to the Fear Gorta rising again and wandering the land.

The Merrow

“She’s not your mother. She’s not a woman; she’s not even human. From the moment she went over, we lost her just as surely as if she’d died. They do not live for our benefit. They belong to Themselves.”

-Ananda Braxton-Smith, “Merrow”

The Irish version of one of the most popular and well known mythical creatures out there is not quite as evil as similar creatures from other cultures, but also not as harmless and fun-loving as the more child-friendly modern variations. Here’s Irish Mythology’s answer to the mermaid.

Appearance

Unlike the appearance of mermaids, merrows are not beautiful women with the tail of a fish, instead, they have human legs, allowing them to walk on land and not just flop around by the shore.

Unlike humans however, merrows have large, flat feet and webbed fingers which allow them to swim very easily.

Although female merrows are described as stunningly beautiful and are highly desired by men on the shore, their male counterparts are not so lucky.

Described as exceptionally hideous sea creatures, merrow men don’t possess any human features, but instead have ‘pig-like’ features and long, pointed teeth.

Behaviour

Unlike the Merrow’s Greek counterparts, the Siren, they don’t seem to exist purely to lure and kill fishermen and sailors. In fact, many stories describe them as friendly and modest creatures.

In order to be able to swim through the ocean current, merrows need to wear some special clothing. In Kerry, Cork, and Wexford, they have to wear a small, red cap made of feathers, and in the more northern regions, they wear sealskin cloaks. When they want to come ashore, they have to discard their clothes near the shore.

Due to their extreme beauty many human men want to have them as wives, and this could be achieved by finding and hiding their special clothes. This forces the merrows to become their wives, and they can not leave until they find the hidden clothes again. After the clothes are found, the urge to return to the sea becomes so great that they abandon their human children forever.

Some legends say that female merrows actually seek out human men for marriage since merrow men are too hideous to marry. Just like sirens, they use their beautiful music to entrance men and drag them beneath the ocean. Although sometimes they mate with human men on the shore.

Origins

Author Thomas Crofton Croker’s book Fairy Legends laid the groundwork for the folkloric treatment of the merrow. This book was translated into German by the Brothers Grimm. Croker’s writings were rehashed by writers like W.B Yeats, Thomas Knightly, and John O’Hanlon. This is where the commonly known characteristics of merrows stem from.

Where the original myth comes from, we don’t know, but it was likely a myth created to explain the disappearances of young men at sea.

Legends

There is a story involving merrows in the Dindsenshas, an early Irish piece of literature describing the origins of place names. The story describes the death of Roth son of Cithang, who was devoured by merrows near the English Channel, and only his thigh bone was left, which washed ashore in Waterford, which was then given the name ‘the port of thigh’, or ‘Port Láirge.’

Irish mythological creatures are truly unique, and have served as inspiration for many creatures and characters in fiction for thousands of years. These creatures give an insight into the people, the culture, and the history of Ireland in a way that isn’t really achievable without them. Unfortunately, these insights show us just how dark and full of death and misery Irish history is. But at least we got some cool scary stories out of it.