Irish Artists: The Duality of Harry Clarke

The Duality of Harry Clarke: A master stained-glass artist and a controversial illustrator

Harry Patrick Clarke remains one of Ireland’s greatest stained glass artists and illustrators. His vivid imagination, combined with marvellous originality in his subject matters and his execution of the stained glass technique, truly makes him with a leading figure in the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement.

Clarke and his preferred media – stained glass and book illustration – were critical in establishing early 20th-century Irish art movement. While analysing his work, most of which is public, it can be observed that it is formidable, with a hint of paranormal, and his intricate artworks stand out, different in several ways from his contemporaries.

Even though Clarke lived, worked, and created his art amid turbulent periods within Irish history, a deeper study into his darker and controversial world indicates that this is where he thrived as an artist primarily due to the freedom it provided. These artworks shocked the highly conservative religious communities and even refused to display a lot of Clarkes’ work as they were simply repelled by such “startling excess”.

When Clarke started producing his stained-glass art works, Ireland was recovering from centuries of British rule, and the country wanted to re-establish its traditional Gaelic culture. Consequently, nationalist movements started emerging that heavily focused on Celtic themes and the Gaelic language. His early stained work has often been set with the Irish Arts and Crafts movement, Symbolism Decadence, Art Nouveau and Art Deco.

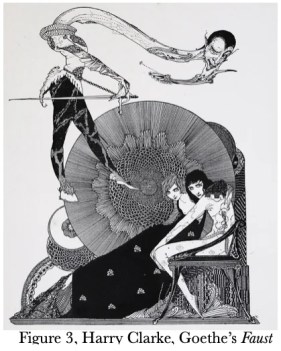

After analysing his black-and-white illustrations and drawings, art historian Nicola Gordon Bowe refers to them as having “a hitherto psychological intensity”. However, his graphic black-and-white and colour drawings show a different tendency and expression of strangeness. The illustrations gave Clarke immense freedom that he required in order to experiment with the contemporary aesthetic practices that were unavailable to him, as was the case with his stained-glass commissions.

An indicator of this can be observed in the letter Clarke wrote to his friend Thomas Bodkin, on November 1925, one month after releasing his illustrated edition of Goethe’s Faust (October 1925):

“I feel I do not do a book as it should be done. I see my drawings and there is only a hazy background of the Book, whereas the drawings should, as you have so many times said, be subordinate to the whole – or an item in a complete scheme. Unless I am tempted by a good offer, which seems unlikely, I shall just do drawings of such ideas and things that strike me when I am alive; and try to sell them.” (Bowe, Harry Clarke: 258).

The Church commissions, he felt, withheld his true style and his authentic vision which he required to experiment- making him feel extremely frustrated. He did not want to abide by preconceived notions of Irish traditions. Moreover, by the 1920s, his approach to book illustrations changed drastically, from the well-established concepts of the decorative and the beautiful, to new and contemporary art movements like Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and Modernism. His illustrations in Faust indicate various elements in addition to mere aesthetics. It relates to the avant-garde art movements across Europe and makes a crucial statement regarding his methodology.

Clarke admitted that the realm of book illustration gave him significantly more autonomy, which further enabled him to experiment with new artistic styles, ideologies, and philosophies. This was absent in the stained-glass world and the vast amount of restrictions he faced drove him to dedicate his artistic integrity towards illustrations.

Henceforth, Clarke showed signs of automatism, wherein the artist or writer gives up the conscious control of a process to allow his or her unconscious mind to guide the production of work. When the critic, George AE Russell, reviewed Clarkes’ work in Faust, he remarked that the artist’s work signalled a departure from his earlier approaches and his “escape from the influence of Aubrey Beardsley” (Gordon Bowe, Harry Clarke: 257).

His work in Faust can also be placed among the then-emerging Surrealist movement. Therefore, analysing this as an experiment with Surrealist theory and methodology, the initial ghastly shocks and ‘negative reviews’ suggest that this could have been his true intentions. Distinctive and contemporary art movements, especially avant-garde, were used to primarily question, challenge, and even mock the existing conservative notions. Clarke’s other works, especially The Geneva Window bear out this opposition, as Bowe argues, wherein this artwork, which was commissioned by the state, was then rejected and shamed, never installed, and was eventually locked away.

Clarke’s early beginnings and Faust: A Dark, Surrealist Fantasy

Clarkes’ frustration with the centuries-old techniques and adherence to conservative traditions can be traced back to the 1920s when he tells Bodkin that “no advance in the techniques has been made since the fiftieth century”. In June 1925, he described how illustrations and drawings freed him and gave him the space he needed to experiment with different art forms. He goes on to say, “I am aware the drawing I put into the heads of my figures is often criticised – what I am really endeavouring to get into the heads is an element of humanity – or, in other words, to get away from the rather stuffy meaningless faces usually put into stained glass …” (Bowe, Harry Clarke: 246).

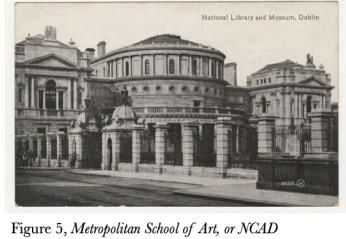

Having been born and brought up in a commercial stained-glass window business, Clarke received and lived through a remarkable period of art education in Dublin. He studied life-drawing at the Metropolitan School of Art with William Orpen and was trained in stained-glass by A.E. Child. Child was also the former assistant of the famous British stained-glass artist, Christopher Whall.

His time spent in Dublin helped him conjure up Ireland’s Arts and Crafts stained-glass industry. Pre-revolutionary Irelands’ ideals and culture gave way to Clarke’s first major commission, which was a series of 11 windows for the Honan Chapel in County Cork.

These awe-striking windows were highly significant in establishing a good reputation for Clarke’s skilled craftsmanship and authenticity. Several of these windows were displayed in June 1916 and received numerous positive reviews. The Irish Times (30th June, 1916) reported that “the windows, in the opinion of some of the most competent critics, rival in beauty some of the most remarkable products of Continental art”.

However, by the 1920s, Clarke rebelled and became a controversial figure, going against the “establishment” after he discovered book illustrations. His images were described as “grotesque” and “degenerate” and, in the year 1925, with the printing of Goethe’s Faust, Kelly E. Sullivan links these illustrations of death, doom, and decay to Clarke’s own struggle with the eventually fatal disease of tuberculosis. This shift into a dark world can also be traced to the backdrop of the aftermath caused by the First World War and Imperial British rule.

However, by the 1920s, Clarke rebelled and became a controversial figure, going against the “establishment” after he discovered book illustrations. His images were described as “grotesque” and “degenerate” and, in the year 1925, with the printing of Goethe’s Faust, Kelly E. Sullivan links these illustrations of death, doom, and decay to Clarke’s own struggle with the eventually fatal disease of tuberculosis. This shift into a dark world can also be traced to the backdrop of the aftermath caused by the First World War and Imperial British rule.

The Geneva Window and his death

Unfortunately, Clarke led a short life, yet he was able to make, create, and solidify his legacy in this short period. He managed to create a lot of art during his adult life even though, for the most part, he struggled with ill health. He eventually succumbed to tuberculosis on January 6th, 1931.

Wanting to get back to Dublin to spend his final moments in his home country, he stopped in Coire, a small Swiss village, and later spent many months in Davos hoping to get better.

The time he spent in Davos was further affected by the looming uncertainty of The Geneva Window. This project was a major one, but was engulfed in political and diplomatic complications.

The piece had been commissioned by the International Labour Court in Geneva and was an eight-stained glass panel that made a concentrated visual of a 20th-century Irish literary image, but this was quickly received as a negative, obscene, and false representation of Irish culture.

Róisín Kennedy successfully pieced together how Clarke came to be commissioned by the government to create this gift for installation. Clarke envisioned, in total, 15 scenes from works by Irish writers as “an evocation of work as an imaginative and creative endeavour”. Many of the images were deemed as erotic, and were not in terms with the Catholic teachings and were questioning of Catholic principles on sexuality.

Eventually, even though the government did not intend to display it, it was acquired soon after Clarkes’ death. It is now on public display in the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami, USA.

Clarke lived, worked, and created an extraordinary period in Irish history. Whether it was the Celtic revival, the year of 1916, the War of Independence, or Free State being established, it’s fair to say that he did not, or rather would not fit into any major cultural narrative that was relevant during this era. Many critics and commentators saw modernism as the future and as something progressive, henceforth, they deemed Clarke as too conservative. This ignorant view also casts him as merely a disciple of Aubrey Beardsley, who, in fairness, was an important figure for Clarke.

Clarke’s famous ‘glasses’

Another illustration worth analysing is his 1926 sketch for a commission that was initially intended for the League of Nations building in Geneva, but was later declined for showcasing too much drunken revelry.

Clarke’s inky watercolour, The Magic Glasses (c.1926), is a perfect example of his interest in the decadent and dissolute – it was a sketch for one of the sections for a window that had been commissioned by the Irish government in 1926 for the International Labour Court in the League of Nations in Geneva. When Clarke finished this piece, the government officials rejected it as they were afraid of possible controversies it would attract from the conservative public. Clarke died from tuberculosis in 1931, whilst negotiations with commissioners were still in progress, and, consequently, the window never made it to Geneva due to the Irish government’s outright refusal to partake in this process.

The eight preparatory watercolours for the eight window panes that are in Miami remain in the heart of Ireland in the Dublin City Gallery – The Hugh Lane.

In this intriguing artwork, it can be observed that three men appear in the top left background. Clarke, portraying himself, is seen with unkempt hair and almost greenish skin which possibly shows signs of illness. Interestingly, the scene is from a movie by F.W. Murnau called Nosferatu (1922), and he is seen standing in front of this scene, and, behind him, the wide-set of eyes peeling at him are Oscar Wildes’.

Many of Clarke’s compositions consisted of figures that were isolated, and there are possible hints of that theme in this art piece as well. But, even more fascinating is the fact that he included another passion of his: the Irish theatre. The central figure, looking somewhat unsteady in the blue plaid shirt, is Jaymony Shanahan, who was a character from the play The Magic Glasses (1914) which was written by George Fitzmaurice. The character spends his days looking through nine differently coloured magic glasses given to him by a fairy to enable him to see a better version of his life. It is a tale of fantasy, imagination, and projection that, at the play’s end, kills Shanahan. Seeing images through glass clearly resonated with Clarke and sustained him until his own untimely end.

Visions of Clarke

There were many peculiar things in the world of the early-20th-century Irish artist. The great Irish writer, George Russell, saw Clarke as “one of the strangest geniuses of his time” who “might have incarnated here from the dark side of the moon”. WB Yeats called Clarke “Ireland’s greatest artist in stained glass”.

Clarke exuded the aggressive brutality of the 20th century along with his own idiosyncratic fantasies. He seems to have been heavily influenced by the idea of crucifixion and the notion of mortality. For example, he stripped down for photographing his own crucifixion and in these revealing photographs, his body seems to be echoing the trauma of famine, revolution, and war – as well as auguring the wasting disease that would eventually kill him.

Furthermore, it is also worth evaluating how his “decadent” thought process was significantly dissimilar from his contemporaries. Unlike the Romantics, who praised visually-pleasing aspects of the world like nature and beauty, the decadents took a completely contrasting approach and looked down on the idea of a God and higher spiritual realms, unlike devout Christian believers. Finding themselves submerged in their own melancholy, uneasiness, and a sense of incompleteness, they tried examining the unnatural as their only hope. Poems and illustrations, therefore, were filled with images of jewels and instances of extreme slyness, such as masks, gold-works, and particularly perverse examples of natural phenomenons.

Critically acclaimed Aubrey Beardsley, who wrote “The Ballad of a Barber”, creates a similar scene in both versions of his “Toilette of Salome and in The Coiffing”:

Clarke successfully follows in the steps of his master, not only in the representations of elaborate wigs in his illustrations to Charles Perrault’s version of “Sleeping Beauty” and “Cinderella”, but also in “Anyone but Cinderella would have dressed their heads awry.”

The main characteristics of the “decadent” were to try to escape the stagnant human apathy by emphasising on evil which was seen as unnatural and what also led to a movement within the visual arts that glorified and proudly presented the grotesque. These characteristics were found in works by both illustrators, for example in the figures in the foreground of Venus at her toilet, the musician in The Stomach Dance, and in Enter Herodias. Conclusively, Clarke’s drawings for Faust bring to light many ‘grotesques’ in his illustrations which he further used for fairy tales.

Clarke’s Conundrum

Harry Clarke’s illustration work for Swinburne’s Faustine is a good example that indicates his admiration of raw sexuality, particularly accentuating on sex, death, and vivid imagery engrossed in the world of grotesque. For example, he juxtaposes a female nude, skull, and vulture in Beardsley’s The Platonic Lament and The Climax for Wilde’s Salome:

Beardsley’s illustrations are full of heterosexual male desires, but they are sometimes overtaken by his constant use of androgynous figures. Sometimes, a lady’s thick neck and vivid jawline can easily be confused as a figure of the opposite sex, like in The Dancer’s Reward where John the Baptist has been made to look very feminine.

For his work in the poems of Swinburne, Clarke illustrates and sketches an androgyne for the page decoration, and similarly repeats the theme in several of his images for Perrault’s Fairy Tales . A prime example of this can be seen in “The prince enquires of the aged countrymen”, wherein its only male biology that affirms the reader that the figure might be a male even though his outer garment looks very much like a gown, with the ornate feathers and decorations that make him look feminine.

Clarkes’ representation of female figures also screams perversity. The first image shows a wide-hipped woman, who appears naked and can be seen staring straight out at the viewer. The page decoration that Clarke did shows a clothed man and nude woman in a boat with the man’s face leaning against the woman’s breasts as he grabs her thighs. Clarke draws the woman’s arms behind her as she throws her head back.

Conclusion

Conclusively, when we observe and study the life and work of Harry Clarke, even now, his images remain equally startling. It is worth mentioning again that all of his artwork was created amidst a very repressive culture and, consequently, with repeated opposition. Clarke seems to have tried to resemble himself in his pictures, wherein he portrayed an innocently narcotic-like look, resembling an animal more than a human. Philip Hoare, who writes for The Guardian, discovered, while researching Clarke’s work for his book Rising Tide Falling Star, that Clarke drew his marine-inspired images from the ornate and intricate 19th-century glass models made by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka.

In the book Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of The New Irish State, edited by Angela Griffiths, Marguerite Helmers, and Róisin Kennedy, published by the Irish Academic Press, the authors argue that the time period was indeed “a degrading and dark era in Irish history”. But, in this dark, uninspiring era, the work of Harry Clarke emerged and truly glistens. His art reflects an Irish society “much more cosmopolitan, sophisticated and aesthetically aware than has normally been acknowledged”.

Amazing write up…looking forward for more..

Thank you!!

Awesome floored

Thank you so much!!