A Brief History of the Irish Language

The history of the Irish language is somewhat tricky. What can be confusing for tourists or migrants coming into Ireland is why we don’t speak the language. There are very few parts of Ireland where Irish is spoken, with the general population speaking English. What may also be confusing is why we’re so adamant on keeping the language alive when so few areas actually speak it. Why it’s still compulsory in primary and secondary schools. The answer is rather complicated, so here’s a brief history of the Irish language, and the impact it has on today’s education.

The Irish Language throughout history

Development of the Irish language

The earliest form of Irish, known as Primitive Irish or Archaic Irish, was seen on Ogham Stones in the form of inscriptions. The inscriptions translate for the most part as people’s names. The next evolution of the Irish language was called Old Irish, similar to how the English language has Old English. Old Irish had more characteristics of full language that Primitive Irish lacked, including broad and slender consonants, inflections, and the letter “p.” Old Irish gave way to Middle Irish in the 10th Century, and Early Modern Irish came in the 13th Century and was used until the 18th Century, where it migrated and was used in Scotland also. It eventually became Modern Irish, which is what is taught in schools today.

If you want a more in-depth review of the history of the Irish language, read here.

English Influence

Britain invaded Ireland in the late 12th Century, and fully colonised it in the 16th Century. Opinions on the Irish language shifted depending on the ruler. In 1367, a law was passed that forbade English colonists speaking Irish. Queen Mary I, who reigned between 1553 and 1558, wanted to abolish the Irish language, and encouraged the speaking of English, in order to fully instill the British culture on the island. Her successor, Queen Elizabeth I on the other hand, was fascinated by the language, and as a connoisseur of foreign languages, she wished to understand it herself. Despite efforts to reduce the speaking of Irish, in 1800, it was still the dominant language and was important for matters of politics and the law. As Ireland sought independence from Britain, it became even more important.

Irish language in the 20th Century

Ireland’s struggle for independence came to a head in the 20th Century. One of the long-standing arguments as to why it shouldn’t be a Free State was that it didn’t have its own language. By this stage Irish was already dwindling, largely due to The Great Famine in 1845. More than one million people died and about two million emigrated. With the lost population, the language began to disappear also.

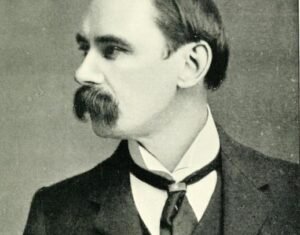

Douglas Hyde, who went on to become the first President of Ireland, saw the importance of the Irish language. He believed that Ireland had a unique culture that, despite Britain’s presence, that was worth preserving, and integral if they hoped to ever become a Free State. He was the co-founder of the Gaelic League, which ran from 1893 to 1915, an organisation that sought to revive the Irish language as well as Irish culture. It is because of his efforts that Irish is still taught in schools, and remains on major sign posts, such as road signs or in airports.

The Irish Language in Education

Primary School

In Ireland you can’t even become a primary school teacher if you don’t have a minimum of a H4 grade (between 60-69%) in Irish at Leaving Cert level. You begin learning Irish as early as Junior Infants, the lowest class in Irish primary schools, and you begin learning correct grammar and sentence structure as early as First Class. At this age, building vocabulary is the main goal.

Secondary School

As with most subjects, the leap in difficulty for learning Irish is huge in the transition from Primary School to Secondary School. It remains one of your compulsory subjects the whole six years, along with Maths and English. In Secondary School, speaking Irish and understanding spoken Irish becomes more important, with the introduction of the Aural exam at Junior Cert level, and the Oral Exam at Leaving Cert level. Irish can be taken at Higher Level, Ordinary Level or Foundation Level and where some classes are only taught two or three times a week, Irish is taught everyday.

There are some schools called Gaelscoileanna that teach everything through Irish. The students that attend these schools are fluent in the subject. There are 72 of these schools in the Republic, with 14,500+ students. In comparison, there are 381 English speaking Secondary Schools in the country, with 201,700+ students.

University

It is not compulsory to take Irish at University level, although some college courses will require you to have gotten a certain grade in the subject. At this stage of learning, the majority of students drop the subject, and effectively never speak it again.

Gaeltachts

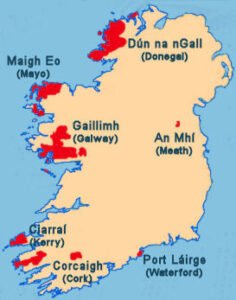

There are some parts of Ireland where Irish is still the predominant language spoken – these are called Gaeltachts. They reside mostly on the west side of the country, in counties such as Donegal, Mayo, Galway, and Kerry. This was because colonising began in the East, and the West was affected by the shift in language much slower. There are other counties that have small Gaeltacht regions too, such as Waterford, Cork, and Meath. In Secondary School, particularly in 2nd Year and 5th Year, it is common for students to go to Gaeltacht areas, generally for a period of three weeks, to immerse themselves in the language in order to achieve a better result in their Junior and Leaving Cert exams in 3rd and 6th year respectively.

The total population of Ireland is 4.9 million. The total population that speaks Irish is 1.7 million, and the population in Gaeltacht areas is only 96k. For a long time Irish has been a dying language, with less and less people speaking it every year.

You can learn more about Gaeltachts here.

A Personal Experience with Learning Irish

Primary School

I was born in County Armagh, Northern Ireland, so I didn’t learn Irish for the first six years of my life. As one of the six counties still a part of the United Kingdom, it wasn’t an option in schools. However, when I moved to Dublin, and entered primary school, I began learning Irish. I could have been made exempt, given my background, however, I’m glad my parents ensured I learned it, as I have now lived in the Republic of Ireland for 19 years. I saw it as something that helped assimilate me into life in Dublin.

I was born in County Armagh, Northern Ireland, so I didn’t learn Irish for the first six years of my life. As one of the six counties still a part of the United Kingdom, it wasn’t an option in schools. However, when I moved to Dublin, and entered primary school, I began learning Irish. I could have been made exempt, given my background, however, I’m glad my parents ensured I learned it, as I have now lived in the Republic of Ireland for 19 years. I saw it as something that helped assimilate me into life in Dublin.

Secondary School

Irish became dramatically more advanced in Secondary School. In the same year, I started learning Spanish, and although I had six extra years of learning Irish, I found Spanish came more naturally to me. Irish remained difficult and complicated, and because I struggled to learn it, I began to resent it. For whatever reason, in many schools, Irish is poorly taught, and many students begin to grow annoyed with it, knowing they’ll likely never use it again once they leave school.

Irish became dramatically more advanced in Secondary School. In the same year, I started learning Spanish, and although I had six extra years of learning Irish, I found Spanish came more naturally to me. Irish remained difficult and complicated, and because I struggled to learn it, I began to resent it. For whatever reason, in many schools, Irish is poorly taught, and many students begin to grow annoyed with it, knowing they’ll likely never use it again once they leave school.

I studied Irish at Higher Level, as I needed the Higher Level points to get into my desired course, and ended up getting a C1 in the Leaving Cert (between 65-69%). I was happy with this mark, but it seems unusual that I got a B2 in Spanish (between 75-79%) which I had been learning for half the amount of time, when I put the same effort of studying (and probably more so for Irish) into both languages.

Gaeltacht

Like many students, I attended the Gaeltacht in the summer before my Junior Cert year. My friends and I were shipped off to Spiddal in Galway, and lived in a house with a Bean an Tí (Woman of the House) where we were supposed to be monitored for speaking Irish. Monday to Friday we would attend Irish classes and in the afternoons you would play sport or go to the beach. Every evening you attended a céilí, or a dance, and all of this was conducted through Irish. While it was an enjoyable thing to do for the summer, it did little to improve our Irish. We spoke English at the table, with no interference from our Bean an Tí, and only spoke Irish in the presence of the teachers, as speaking English was an offence that could (allegedly) have you sent home. I came back with a tan and new friends, but with no better Irish than I had three weeks previously.

Like many students, I attended the Gaeltacht in the summer before my Junior Cert year. My friends and I were shipped off to Spiddal in Galway, and lived in a house with a Bean an Tí (Woman of the House) where we were supposed to be monitored for speaking Irish. Monday to Friday we would attend Irish classes and in the afternoons you would play sport or go to the beach. Every evening you attended a céilí, or a dance, and all of this was conducted through Irish. While it was an enjoyable thing to do for the summer, it did little to improve our Irish. We spoke English at the table, with no interference from our Bean an Tí, and only spoke Irish in the presence of the teachers, as speaking English was an offence that could (allegedly) have you sent home. I came back with a tan and new friends, but with no better Irish than I had three weeks previously.

In 4th and 5th Year, there were more opportunities to visit the Gaeltacht, but by this stage I had resigned myself to only being mediocre at the language, and I decided to pass. Gaeltachts for older students are much stricter, in order to prepare you for the Aural and Oral exams for the Leaving Cert, which take up a whopping 50% of your final mark. Any affection I had for the language as a child had long since passed and I didn’t fancy spending three weeks studying and trying to speak a language I was already so bad at.

After Education

Now that I’m older, and have been out of the school system for a few years, I feel sad about my lack of Irish. I learnt it for 12 years, and can remember very little of it. Where I was once annoyed I had to learn it, I’m now sad it couldn’t have been taught better. I loved learning Spanish, and because of the way it was taught, I was able to keep up with the work, but for my last few years in school, learning Irish was an uphill battle. More than a third of the students in my year dropped to Ordinary Level, which was the second highest percentage of people choosing Ordinary Level for a subject next to Maths. For something so ingrained in our culture, so important to ensure our independence, that students so often find it too difficult is a terrible shame. They need to overhaul how Irish is taught, start teaching the intricacies of it sooner, if we hope to see it stay alive because clearly something is not working with how Irish is taught in schools. A lot of students love the idea of learning Irish and see its importance, but find it too difficult to grasp.

Ways to Keep the Irish Language Alive

Every year, in the run up to St. Patrick’s Day (17th March) Ireland hosts Seachtain na Gaeilge, or Irish Week. This week is dedicated to celebrating Irish pride and Irish culture, and it has been running since 1901. It has turned into an international phenomenon, with many countries around the world joining in on the St. Patrick’s Day celebrations. Participating in this important week is a way of keeping the Irish language alive.

For children, and young adults, maybe the best way to immerse them in the language is through TV and Radio. In Ireland we have TG4, which is a channel entirely in Irish, and RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta, which is an Irish radio channel. However, from personal experience, I can say these platforms felt outdated to me as a teenager, and besides the odd Harry Potter showing on TG4, there was little you would actually want to watch. As with the education system, these platforms need to be changed and adjusted to reflect today’s youth, and to make Irish something they want to learn, not something they’re just forced to learn.

For children, and young adults, maybe the best way to immerse them in the language is through TV and Radio. In Ireland we have TG4, which is a channel entirely in Irish, and RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta, which is an Irish radio channel. However, from personal experience, I can say these platforms felt outdated to me as a teenager, and besides the odd Harry Potter showing on TG4, there was little you would actually want to watch. As with the education system, these platforms need to be changed and adjusted to reflect today’s youth, and to make Irish something they want to learn, not something they’re just forced to learn.

If you have any thoughts on how to keep the Irish language alive, leave a comment below.